Impressions from a Visit to Western Ukraine

By Medea Benjamín and Ann Wright

After leaving the very successful International Summit for Peace in Ukraine that took place on June 10-11 in Vienna, with representatives from 32 countries participating, Ann Wright and I decided to travel to Ukraine.

We took an 8-hour bus ride from Warsaw, Poland to Lviv, the largest city in Western Ukraine. On the bus we met a young Ukrainian-American woman from California who was volunteering for the summer at a camp for widows and orphans, a Croatian aid worker with an international relief agency, a Norwegian writer traveling to do research for a book. But most of the people on the bus were Ukrainians going to visit their families. Since the Ukrainian government declared martial law, men between ages 18 and 60 h nave not allowed to leave the country in case they are needed for the war effort. So women living abroad, sometimes with their children, go back and forth to visit.

Gazing out the window while our bus passed through miles and miles of rich agricultural land and neat, prosperous-looking villages on the Polish side, we thought about the waves and waves of Ukrainians–women, children and the elderly–who fled into Poland through this very route in the early days of the Russian invasion.

Shutterstock

Poland alone had absorbed an astounding five million refugees! Even more astonishing, there was not one refugee camp. The Polish people welcomed the Ukrainians into their homes. Most refugees only stayed for a short time and moved on to other places in Europe where they had relatives, or returned to parts of Ukraine that are safe. There are now are about 1.5 million Ukrainians left in Poland, which is still a huge number. You meet a lot of them working in the service sector, particularly hotels and restaurants. They struggle not only with leaving their homeland and oftentimes their male family members, but also with the Polish language, which is, as one refugee told us, “impossible to learn.”

When we got to the border, we were concerned that Ukrainian authorities might ask us about the purpose of our visit, which was really just to talk to people about the war. If questioned, we were prepared to mention the humanitarian groups we have worked with, but no one even asked. The border guards simply collected everyone’s passports on the bus and soon returned them all without incident. We were surprised that we didn’t even have to take our luggage off the bus for inspection. Nothing. And suddenly, we were in the country that has been invaded and ravaged by war for the past 18 months.

Arriving in Lviv, we were surprised by all the young men in the streets. We had heard that all men of military age were being conscripted, but that is not the case. They have to register with the military, but they are not called up if they are students, if they work in essential businesses, or if they have any health problems. People told us that the military’s shortcoming is not soldiers, but munitions.

Lviv, which is in the western side of the country, has been mostly spared from the fighting. It’s a bustling city full of trendy coffee shops, lush parks, and fashionable clothing shops. Aside from the presence of soldiers on the streets, sandbags piled up along some of the buildings, and monuments and church windows covered up to protect them in case of attack, there is little evidence of war.

We checked into our modest Ibis hotel, where we were handed a letter saying that any “damage to my life or health as a result of hostilities during my stay in the hotel will be the responsibility of the aggressor country and not the hotel administration.” It went on to cite the importance of air raid alert notifications and the need to go down to the hotel’s bomb shelter if an alert was called.

We signed the letter thinking it was really “pro forma,” as there had been little military activity in Lviv for months. But to our surprise, at 4 a.m. the sirens started blaring. The message on the loud speaker was in Ukrainian, so we didn’t know what they were saying. Tired and thinking that perhaps it was just a nightly routine, we ignored the noise and went back to sleep.

The next morning we learned that indeed it has been a real air raid, and that many of the guests had gone down to the bomb shelter from 4 a.m. until 6 a.m., when they were told it was safe to return. The government reported that some kind of infrastructure had been hit by a Russian drone, but never specified what exactly was hit. We later learned from one of the guests that the target was the main police/intelligence building. We went by the site later in the day and saw the gaping hole in the corner of the top floor of the building where the drone had exploded. Luckily, no one was injured.

Our general impression, which came mostly from random conversations with people who spoke English, is that they are angry as hell about the invasion, they hate Putin and the Russian soldiers, and they want victory–not negotiations. “How you can talk to your rapist?,” was a common refrain.

When we specifically asked about Crimea, people responded that Crimea is an integral part of Ukraine and must be recovered. And yes, they think victory–which for them means recovering every inch of land that the Russians have taken–is possible. That is, of course, what their government has been telling them. Watching local TV, we saw constant scenes of Ukrainian solders blowing up Russian ships, deflecting Russian missiles, and detecting and destroying Russian mines.

People were glad to meet Americans and express their gratitude for U.S. support (in a museum, one of the workers, upon hearing we were from the U.S., teared up, touched her heart and said “We thank Biden”). Knowing that U.S./Western support could not last forever, some said that even if the U.S. stopped sending weapons, they would keep fighting.

But sometimes people let their doubts about a total victory surface. We met two young Ukrainian men in a park one evening as they were downing shots of vodka and coke from plastic cups. One confided, “We want all of Ukraine back, but honestly, I don’t think it’s very realistic. The Russians will not give up Crimea. And that’s why I have no idea how and when this war will end.” His friend told him to stop talking like that, as he could get them in trouble.

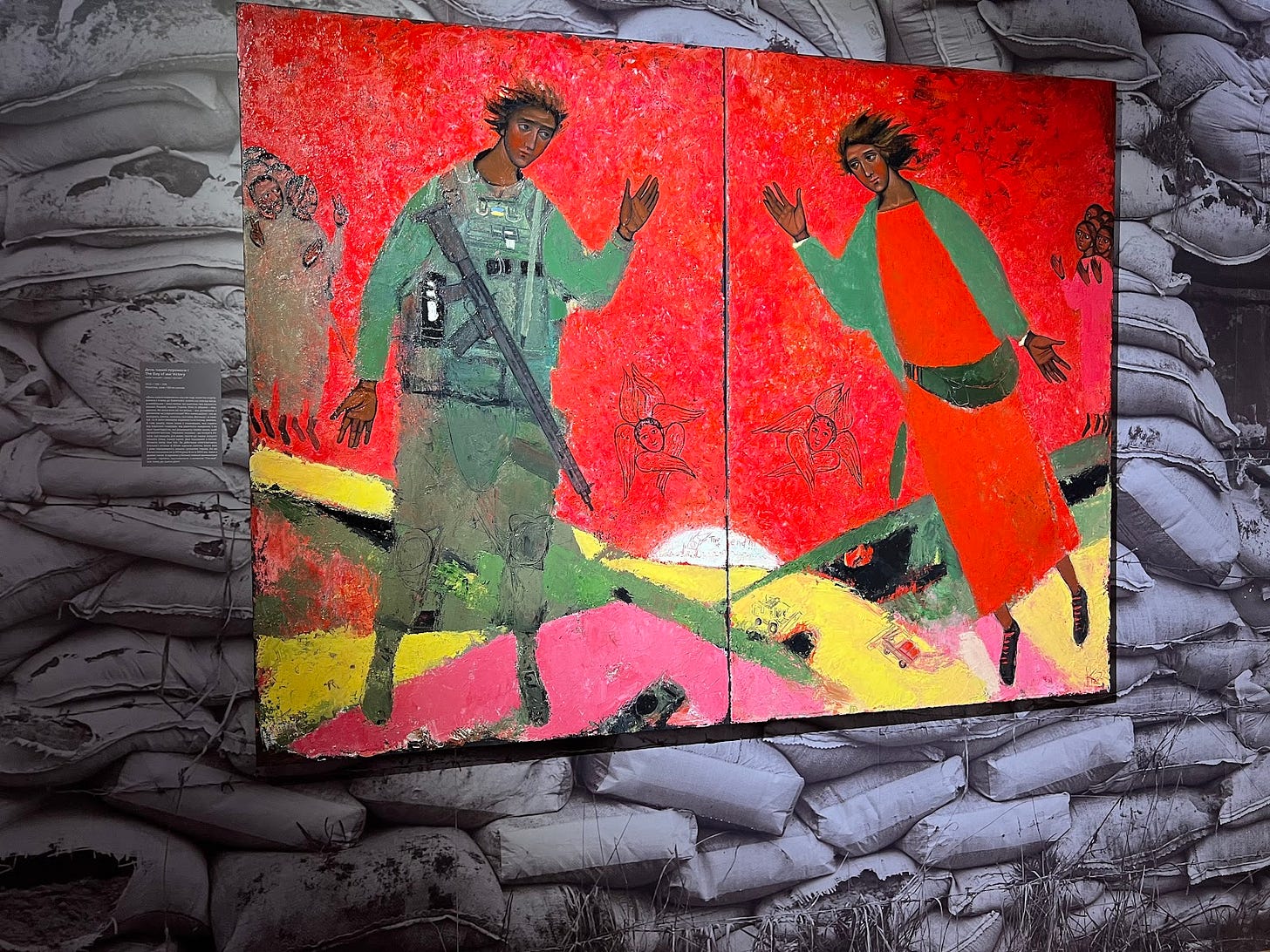

One of the responses to Russian aggression and denial of their sovereignty was a hyper sense of nationalism. Some of the positive manifestations of this nationalism are cultural, such as the ethnography museum that brings students to learn about Ukrainian history or the numerous art exhibits that celebrate Ukrainian painters, past and present.

One particularly haunting exhibit was by contemporary artist Kateryna Kosianenko, whose exhibit, entitled Victory, included a painting where soldiers became angels watching over the villages.

In the evenings, youth groups sing folkloric and patriotic songs in parks and town squares. We caught a troupe of fresh-faced university students, led by an energetic music professor, playing instruments and singing in lovely harmony to the delight of passers-by. One of the students who spoke English told us that their folklore group was formed after the war as part of their desire to demonstrate love for their country. The student’s mother, who was listening, beamed with pride.

Street exhibits extol the virtues of the resistance fighters or tell the stories of refugees who continue to support the Ukraine resistance in their new homelands.

Some of the nationalism, however, has darker tones. While some people seemed able to separate their hatred of the invaders from the Russia people, others expressed hatred of all things Russian, including the language. Stores posted signs saying “The language of the invader will not be tolerated here.” A young woman who used to teach Russian now says she refuses to speak it and called all Russians “garbage.” This is not only worrisome for the future of dealing with their neighbor, but also for the millions of ethnic Russians and Russian speakers who live in Ukraine–many of whom have migrated to this area to escape the war.

There is a strange, hypernationalist restaurant called Kryivka, which had become a tourist attraction long before the war began. It is across from the City Hall but there is no sign on the door; you just have to ask around. Then you knock on the unmarked door, where we you’re greeted by a soldier (in our case, a very brusk, unfriendly soldier) with whom you must exchange the password. He says "Slava Ukrainia” (Glory to Ukraine), the national salute that dates back to the early 20th century, and to gain entry you are supposed to reply “Heroiam slava!” (Praise our heroes). Once downstairs, the decor resembles an underground WWII bunker. You sit on a bench at a wooden table.

The favorite drink at the restaurant is Putin Huylo (Putin is a dickhead), a beer first launched in 2015 after Russia annexed Crimea. The label depicts a cartoonish Putin as a tattooed mafia boss sitting on a throne.

Souvenir shops at the restaurant and nearby stores sell the Putin beer, heart-shaped chocolates with pictures of Ukrainian soldiers, toy grenades and tanks, and t-shirts that show Ukrainians blowing up Russian ships or giving Russian soldiers the middle finger. We got excited when we saw a t-shirt with a peace sign, until we saw that underneath the peace sign were the words “of shit.”

In the early evening of our second day, we visited the cemetery where soldiers from Lviv who had been killed in this war are buried. There were about 500 graves. Most had two photos, one of the deceased as a civilian and one in military mode, and were adorned with flowers and the nation’s Ukrainian yellow and blue flag. Many had another flag as well–the red and black flag that is a symbol of Ukrainian resistance. The black symbolizes the earth and the red represents blood spilled for Ukraine. This flag is often associated with ultra-nationalist groups such as the Right Sector.

Women who looked like mothers and wives of the deceased were busy watering the plants, polishing the artifacts and cleaning their loved ones resting place. Children were bringing flowers to lay at the feet of the fathers they would never see again.

Two days in a row, our relaxed strolls through town were punctured by military funeral processions, where soldiers and civilians would line up outside one of the churches while a van pullled up carrying a coffin. The soldiers would take out the coffin, perform a military salute and then everyone–even those passing by–would get down on one knee to show respect for the deceased. The soldier’s loved ones could be seen weeping as the soldiers carried the coffin into the church for a final ceremony.

It is understandable that people would have an intense sense of nationalism and hatred of the Russians. The tremendous death and destruction that the Russians have perpetrated naturally leads to a desire to destroy all things Russian, and this is also a sentiment cultivated by both the government and the media. But it certainly makes it difficult to contemplate solutions.

Our parting conversation was with a Canadian-Ukrainian visiting family. When we started to ask about peace talks, he put his fingers to his lips. “Quiet,” he said. “You don’t want to talk about negotiations in the midst of a conflict where people are fighting and dying for victory. Indeed, that will be the way this war ends, and you can certainly talk about this outside Ukraine. But here it is considered treasonous and people are not yet ready to hear it.” Hopefully, that day will come soon so that all this suffering and destruction can come to an end.

Photo credits: Medea Benjamin

Medea Benjamin is the cofounder of CODEPINK for Peace, and the author of several books, including War in Ukraine: Making Sense of a Senseless Conflict, published by OR Books in November 2022.

Ann Wright served 29 years in the U.S. Army/Army Reserves and retired as a Colonel. She was also a U.S. diplomat for 16 years and served in U.S. Embassies in Nicaragua, Grenada, Somalia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Sierra Leone, Micronesia, Afghanistan and Mongolia. She resigned from the U.S. government in March 2003 in opposition to the U.S. war on Iraq. She is the co-author of “Dissent: Voices of Conscience.”