Michelle Ellner, CODEPINK Latin America Campaign Coordinator

Chávez isn’t someone I remember once a year, he's someone who shaped how I see the world. But on his birthday, I feel the weight of his absence, and the urgency of his example.

At a time when the U.S. faces rising fascism, corporate rule, and political paralysis, Chávez’s example feels more urgent than ever.

Not just as a leader, but as someone who taught me what it means to be a revolutionary and defy empire. He didn’t just speak of justice; he practiced it in everyday, human ways. He reminded us that caring for others is political. That tenderness is part of the struggle. And that being revolutionary means showing up for people not just in speeches, but in daily acts of love, dignity, and solidarity.

One of my favorite books is Los Cuentos del Arañero, a collection of Chávez’s childhood memories, anecdotes, and reflections. It’s impossible to turn those pages and not feel the weight of a man who led with memory with heart, humor, and a relentless refusal to accept humiliation. His revolution was born in the dust of the plains, in stories passed down by candlelight, in the taste of arepas stretched for twelve mouths, in the quiet resilience of the poor. That same spirit rooted in memory, in dignity, in the voices of the forgotten, shaped not only his rhetoric, but his vision for a new Venezuela.

In a system that told the poor to wait their turn, he said: now.

When he called for a Constituent Assembly in 1999, it wasn’t to fix the system. It was to rupture it. Venezuela’s Fourth Republic had excluded the majority for decades. Corruption and clientelism ruled. The new Constitution, approved by referendum, abolished the elite-controlled Senate, created new democratic mechanisms like referendums and recalls, recognized Indigenous rights, expanded women's rights, and enshrined education, healthcare, and housing as social guarantees.

Still, the most profound shift came in 2001, when Chávez passed 49 laws that restructured Venezuela’s economy:

The Hydrocarbons Law reasserted national control over oil.

The Land Law ended generations of land hoarding by Venezuela’s oligarchy.

Dozens more created protections and opportunities for campesinos, fishers, workers, and cooperatives.

Chávez wasn’t managing a crisis, he was dismantling the architecture of neoliberalism. And he knew it wouldn’t fall overnight. Revolution is not a moment. It’s a practice. A continuous, collective fight against forces that regroup the second you look away.

And the empire responded accordingly: with coup attempts, sabotage, sanctions, and lies.

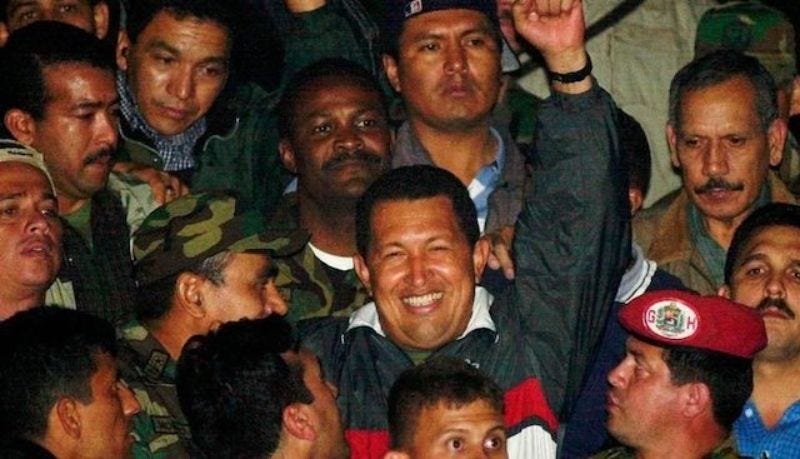

In April 2002, a U.S.-backed coup briefly removed Chávez from power. But within 48 hours, millions took to the streets, and loyal sectors of the military restored the constitutional government. It was one of the clearest examples in Latin American history of a popular mass mobilization reversing a coup.

But Chávez didn’t back down. In fact, he doubled down. After the oil lockout in 2002–2003, it was the people who defended the revolution. Workers occupied facilities, engineers rebuilt operations from scratch, and the national oil company, PDVSA, was brought fully under sovereign control.

From that moment forward, Chávez spoke not just as a president, but as a tribune of anti-imperialism.

He condemned the U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. He stood with Libya and Syria. He expelled the Israeli ambassador after the 2009 massacre in Gaza and called it what it was: genocide. He forged alliances with Cuba, Bolivia, and Nicaragua, and helped create regional bodies like ALBA, UNASUR, and CELAC to promote Latin American integration independent of Washington. Countries with different ideologies found common ground in the push for sovereignty and regional integration.

U.S. movements often speak of saving democracy; guarding institutions, rejecting authoritarianism. But for most working people, democracy doesn’t live in courtrooms or constitutions. It lives or dies in the cost of groceries, the ER bill they can’t pay, or whether their landlord just raised the rent again.

More than 38 million people in the U.S. live in poverty. Over 100 million are burdened with medical debt. Nearly half of renters spend more than 30% of their income on housing and a quarter spend over 50%. In the richest country on Earth, one in five children goes hungry while war budgets rise and billionaires multiply.

While millions in the U.S. go without housing, healthcare, or food, the federal budget continues to prioritize war and surveillance. In 2025, combined funding for ICE and CBP surpassed $31 billion more than the total federal investment in Head Start, public housing, and maternal health. ICE alone received over $9 billion this year, adding to the more than $100 billion it has accumulated since its creation in 2003.

This isn’t a threat creeping in from the outside. It’s a crisis baked into the foundation and sustained by those invested in its survival.

And this is the moment to remember what Chávez taught us: that the real danger isn’t demanding too much, it’s settling for a system that was never built to keep us alive.

We need movements that don’t just resist war, but build peace. That don’t just demand inclusion, but reorganize power. That see Gaza and Detroit as part of the same fight.

Chávez didn’t have all the answers. But he understood the stakes. That if you don’t fight for justice every day, injustice wins by default. That the point isn’t to find perfection, it’s to build power that never stops pushing. He left behind more than a legacy. He left behind a challenge. And a possibility.

That’s the invitation. That’s why we remember.

Happy birthday, Comandante.

Michelle is the Latin America campaign coordinator of CODEPINK.

Michelle was born in Venezuela and holds a bachelor’s degree in languages and international affairs from the University La Sorbonne Paris IV, in Paris. After graduating, she worked for an international scholarship program out of offices in Caracas and Paris and was sent to Haiti, Cuba, The Gambia, and other countries for the purpose of evaluating and selecting applicants. Subsequently, she worked with community based programs design to promote productive endeavors in Venezuela and then served as an analyst of U.S.-Venezuela relations.