Traveling to Prove China Is Not Our Enemy

By: Dee Knight

“China Is Not Our Enemy” was the theme of a ten-day visit to China in early November. The visit was designed to find and highlight a path to common prosperity and a shared future between China, the United States, and the rest of the world. Visiting China made me believe peace is possible.

We flew from JFK to Taipei to Shanghai. Then we took a “bullet train” to Beijing. From there we flew to Urumqi and Kashgar, Xinjiang. Then back to Urumqi to Changsha, Hunan, and from Changsha to Shanghai. Then back to Taipei and from there to JFK.

1. Taiwan is part of China.

Getting to China from the USA is easier now than it was centuries ago for Marco Polo when he traveled from Venice by camel over the old Silk Road. We boarded a jumbo jet at 1am November 1 at Kennedy Airport in New York — actually 1pm in Taiwan and China, which are 12 hours ahead of New York. The flight was a mere 17 hours, so we landed at about 6am November 2. We flew nonstop through northern Canada, then down past Japan and Korea to reach Taiwan. Service on the China Airlines jumbo jet was impeccable — two main meals, enjoyable movies, and plentiful snacks with beverage service.

Visiting Taiwan enroute to mainland China reveals something nearly everyone agrees on: Taiwan is very much part of China. Both Chinese governments agree, and the US government has shared this view since at least 1979, when US President Nixon and Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping signed a treaty to that effect. It makes you wonder why the US is pushing for Taiwan to be “independent” of the mainland, spending billions to arm it to the teeth, and sending war ships through the Taiwan Strait, thus violating China’s territorial waters, at the risk of triggering a flareup to war at any moment.

Before landing in Taipei we spoke with a Chinese couple who were part of the original post-WW2 migration from the Mainland to Taiwan after the Red Army defeated Chiang Kai Shek’s Kuomintang (KMT). Chiang transferred what was left of his army, plus thousands of camp followers and businesspeople across the strait, and took over the Taiwan government with US backing. There was no pretense of democracy — Chiang staged a military takeover and set up a dictatorship that lasted till his death in 1975, always with lavish US support. It was much the same in the southern half of Korea following Japan’s surrender at the end of WW2. There the US backed one dictator after another until the 1990s, when massive popular protests led to brief periods of democratic government — in each case ultimately suppressed by military takeovers backed by the US. Recently Biden held a summit with the leaders of Japan and South Korea to forge an alliance against China and North Korea.

Our Taiwanese chatting partners told us Nancy Pelosi’s recent visit to Taiwan resulted in a major transfer of TSMC, Taiwan’s very large semiconductor manufacturing business, to Arizona. They said many Taiwanese consider this transfer to be a virtual theft of one of Taiwan’s most important economic resources. It threatens a huge business in chip sales to mainland China, which is Taiwan’s largest trading partner. South Korea’s new far rightwing President Yoon actually refused to invite Pelosi to Seoul at that time, evidently concerned that her visit could cut into South Korea’s crucially important trade with China.

It’s really only the US neocon leadership that wants to isolate China by cutting off trade with its east Asian partners. So far the effort hasn’t worked, and is likely to backfire the way US and European sanctions against Russia have, harming US “partners” much more than the targeted “enemy.”

Chinese in Taiwan are very much part of China, just like the people of Hong Kong, where the US and UK tried to sponsor a color revolution that flopped. In both cases the official US narrative has been that it’s “protecting democracy against authoritarianism.” China seems to have more genuine democracy than has existed in the parts of the country the US has been trying to strip away. (Before the 1997 treaty with Great Britain which restored Hong Kong to the mainland, the territory was run by a British Governor General, appointed by Her Majesty the Queen of England.)

I found the Taiwanese we encountered undistinguishably Chinese, and very comfortable with their Mainland cousins. I gather that mutual exchanges of people and trade are thriving. They could, of course, thrive more and better if the US would remove its military and quasi-diplomatic obstacles.

2. Shanghai!

Arriving in Shanghai is amazing. Centuries old, it’s ultra-modern, with past and present living comfortably side-by-side. We stayed in the famous French concession, which French colonists occupied in the mid-nineteenth century, as part of the spoils of victory in the Opium War. While it was the British who invaded and won that war for the “right” to force Chinese to import opium from British India, as soon as the Brits beat down the barriers of trade their fellow colonialists from Europe and America quickly joined the rush for the potentially lucrative China market. Together the colonial powers forced China’s weak government to cede control of trade in both Shanghai and Beijing, the northern capital. Now the “International Settlement” sits alongside the French Concession. It was the result of a merger of the British and American concessions, where the streets had signs saying “No Chinese or Dogs Allowed.”

The main streets in Shanghai’s French concession resemble the wide boulevards of Paris, but traffic whispers along — about half the cars are electric, and nearly all the scooters are. They share the curbside lane with bicyclists riding “bike-shares.” There’s an aura of prosperity in this neighborhood, due to middle-class Shanghainese professionals and businesspeople flocking to take over the area, replacing the colonials who departed after China “stood up” in 1949. (China’s “mixed economy,” following Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Up, is much in evidence in Shanghai.)

Underground, the metro hums along: more than 20 lines rival the extent of New York’s MTA, and humble it for cleanliness, courteous service and safety. All the stations I saw have escalators, elevators, and super-clean floors. They also have moving barriers between the passenger platforms and incoming trains, to protect riders.

We visited the famous Jewish Refugee Museum, just outside the French concession, which relates the stories of more than 200,000 Jewish refugees who found safety after escaping Nazi terror in the 1930s. Among the thousands of desperate people who benefited from Shanghai’s openness and lack of prejudice, we found one story especially interesting: of a Jewish doctor who joined Mao’s Fourth Route Army and set up field hospitals in its Yan’an command center in the caves of north-central China during the war against Japanese occupation before and during World War 2. There were also stories of Jewish business families like Sassoon and Blumenthal, as well as musicians and composers who helped enrich Shanghai’s already thriving culture. The evidence of this pro-semitic Chinese legacy provided contrast for me to recent US media reports of China’s official response to Israel’s bombing of Gaza. The reports called it “anti-semitic” that China’s leaders refuse to justify the Gaza bombardment, which has killed thousands, after Hamas militants broke through their ghetto barriers in surprise attacks.

We also visited the Comfort Women History Museum at Shanghai Normal University, where evidence is preserved of imperial Japan’s abuse and torture of more than 200,000 Chinese and Korean women during the Japanese military occupation of Korea and much of China in the first half of the 20th century. It’s a horrifying story that is really part of an even larger one, which includes imperial Japan’s effort to take over most of Asia during that period. The shock and shame of the Comfort Women system was overshadowed by the Nanjing Massacre of 1937, when the Japanese invaders slaughtered hundreds of thousands of people in this city that had been China’s capital under Chiang’s Kuomintang leadership.

For this observer from the USA, the stories of the Comfort Women system and Nanjing Massacre provide perspective to Joe Biden’s recent summit meeting with the current Japanese and South Korean leaders to forge a military alliance against China and North Korea (the DPRK). In a very real sense, this alliance is merely a continuation of 75 years of US efforts to reverse the Chinese Revolution, which has involved a long-term campaign to rebuild and bolster Japan and South Korea as “force projection” against China. This campaign includes dozens of US military bases in both east Asian countries, where the abuse of modern-day “comfort women” near the US bases is really a continuation of Japan’s shameful program of sexual slavery against Asian women.

All this provides contrast to China’s very different official memory of the Korean War of the early 1950s, which ended in an armed truce, after half a million Chinese volunteers helped Korean liberation fighters repel the US invaders and force the division of Korea at the 38th parallel. That story is detailed in I.F. Stone’s Hidden History of the Korean War, recently re-issued by Monthly Review Press after decades out of print. It’s also told in the 2021 Chinese film, The Battle at Lake Changjin (accessible online in the US). The point of that film — one of the most popular in Chinese movie history — was that the US should have no illusions about an easy victory against the Chinese and their allies in the region. Today, of course, these allies include both North Korea and Russia, as well as the 150-plus partners in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), who recently held a huge 10th anniversary summit in Beijing.

Peace and “common prosperity for a shared future” were main themes at the BRI celebration, just as they were at the BRICS convention last August in South Africa. At that event BRICS membership expanded to include a large percentage of the world’s top oil producing countries, including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia, China and Brazil. This strong emerging global trade group provides assurance against any fantasies US and NATO leaders might have of crimping China’s energy supplies. And the increasing non-dollar trade among BRICS and BRI countries puts a dent in US efforts to use sanctions as weapons. This multipolarity can be seen as writing on the wall: dollar hegemony will soon be over. War ships and threats in the Taiwan Strait, South and East China Seas, and ports across the globe will become less and less effective.

3. The “Bullet Train” to Beijing

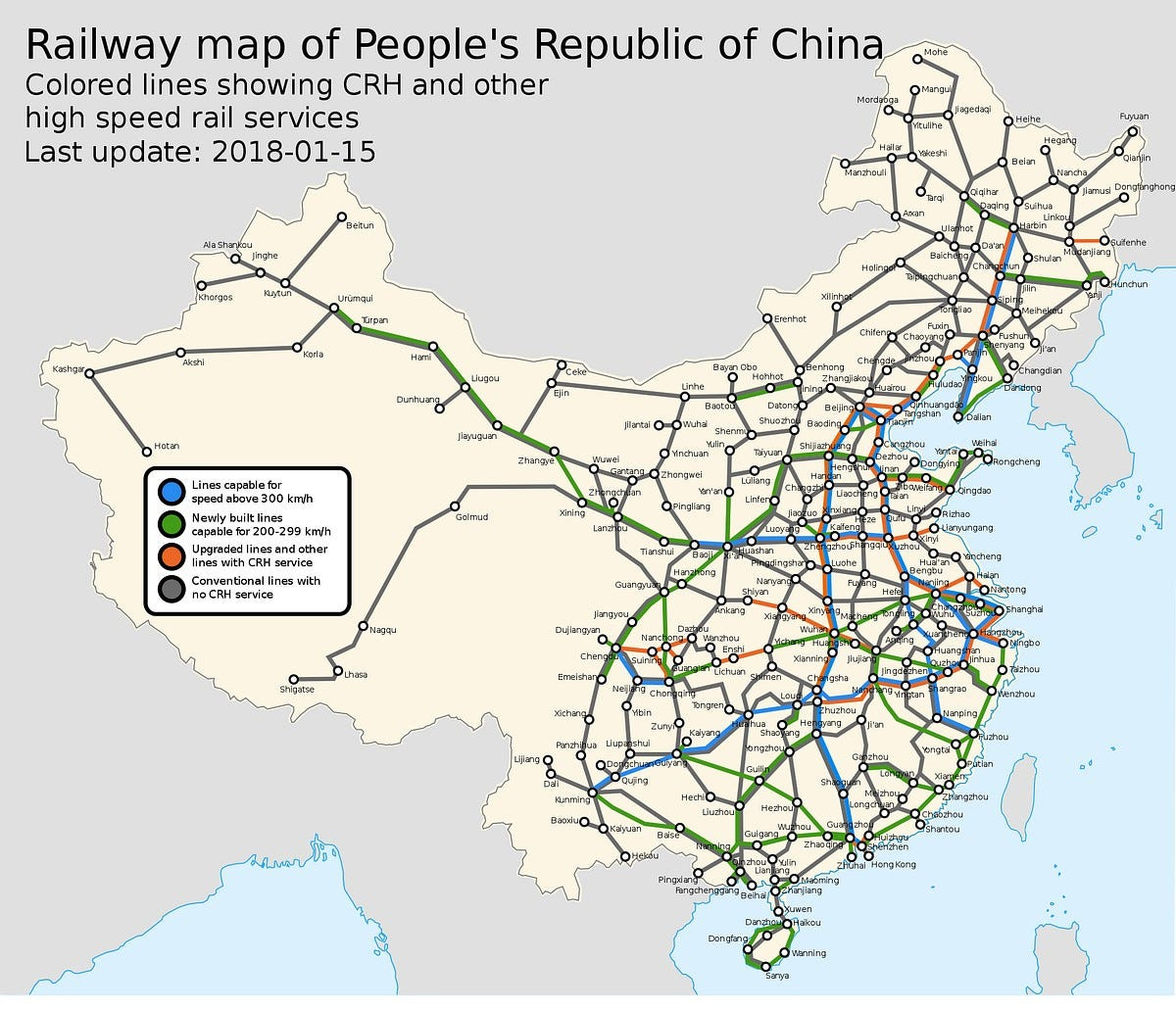

We caught an early morning train from Shanghai to Beijing, which nearly “flew” there in just four hours — half the time it used to take. By air the trip takes two hours, but if you factor in airport hassles, the fast trains are often a better choice. These bullet trains now connect all of China’s major cities, following the gigantic infrastructure projects of recent decades. The US has no bullet trains, and can’t seem to find the financing for them, especially since the profit potential in military production is so much higher. Europe has some very good fast trains among about a dozen cities, but none of them are as fast as China’s. While the US and European economies hit the skids in 2008 and thereafter, China’s central planners went on an infrastructure binge, building trains, metropolitan subway systems, ports, highways and bridges linking the country together. With the BRI the same infrastructure craze has spread across central and western Asia to Europe, as well as across Africa and even Latin America.

A hundred and fifty years ago the US went on a railroad binge that was a major factor in the industrialization boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But those days are long gone, replaced in large part by a military-industrial complex allied with “FIRE” — the Finance, Insurance and Real Estate oligarchy that has taken charge of the US economy, as described by economist Michael Hudson.

Where does China find the capital for all this development? Part of the answer is its far lower military budget compared with the US. Another part is its very favorable trade balance with the big capitalist countries, due to its lower manufacturing production costs. While low labor costs are a key factor, of course, it’s worth noting that Chinese workers’ wages have doubled, and then doubled again in recent decades. And all the infrastructure development has helped efficiency across the Chinese economy. Interestingly, lots of US and European capital has flowed into China to take advantage of lucrative prospects in the world’s largest manufacturing country. Both Elon Musk, the electric car magnate, and Bill Gates of Microsoft, as well as senior western bankers, have been invited guests of President Xi Jinping’s charming hospitality recently — in contrast to high Biden administration officials who have tended to come bearing threats instead of attractive offers of peace and common prosperity.

“Not on my watch” were Biden’s words in response, early in his presidency, to the possibility that China’s economy would surpass the US. Apparently basic math eluded the US president. He couldn’t seem to process the fact that a country with about four times the US population, a much bigger manufacturing base, and average annual economic growth between five and ten percent in recent decades, was bound to have a bigger and more influential economy in due course. Now it’s happening, and Biden & Co — as well as Trump & Co — are freaking out. They should calm down. We really don’t need a war over this. Cooperation, common prosperity and a shared future make much more sense. That formula has found warm welcomes across the globe. It even includes major initiatives in green development, where again China is leading the way. It has more solar and wind energy generation than the rest of the world combined. And while it still uses more fossil fuel for energy than non-polluting sources, Xi Jinping has pledged that by mid-century fossil fuels will be phased out. That would be an accomplishment worth emulating. It’s much better to save the world from burning up than continue with the current US craze of military brinksmanship!

4. Beijing’s Forbidden City and Museums

A world-class capital city, Beijing is really overwhelming, with the enormous expanse of Tien An Men Square, the imposing seat of government in the Forbidden City, the many museums and teeming streets. Our guide chose the Communist Party History Exhibition Hall, and the May 4 Movement’s museum at Peking University. They were great choices for me, with my proclivity for red tourism. In a way it’s what we came for, along with just “seeing everything for ourselves.” Most of what we saw at street level was the calm and very normal bustle of city life, with people coming and going in all directions, heading to and from work or going to restaurants, including McDonald’s and Starbucks! Electric scooters and bicycles hummed along the curb lanes on all major streets. We did in fact visit China to see how the people live and feel their rhythms, so there was no disappointment. But we also came to learn more about the history and current reality of this super-interesting socialist country, with Chinese characteristics (and some capitalist characteristics, too).

The CPC celebrated its 100th anniversary recently, so the party’s history exhibition was jammed with highly visual reproductions of its heroic moments, like the Long March, which followed its bloody 1927 defeat in Shanghai after the Kuomintang cancelled its United Front policy. Every Chinese school child knows of the Long March and its legacy: the emergence of Mao Zedong as party leader alongside Chu De, founder of the Red Army, as the two leaders took the party of the working class into the sea of Chinese peasantry while fighting for survival against an attacking KMT-war lord military force. Then they re-forged an alliance — in spite a total lack of trust — with the KMT against the invading Japanese imperialist army. Then they launched the revolutionary land reform program by mobilizing peasants to take over the land and dislodge the landlords. All of this makes for splendid revolutionary history, well before the reds actually routed the KMT and sent them fleeing to Taiwan, then marching to Beijing where Mao ceremoniously declared that China had “stood up” after a century of humiliation.

Viewing the history of the May 4th Movement was deeply moving. For me May 4 brings back vivid and emotion-laden memories of our own May 4, 1970, when antiwar students shut down campuses across the US in protest, first against Nixon’s savage and grossly illegal bombing attacks on Cambodia, then also against the killings at Kent State and Jackson State. China’s May 4 Movement started in 1919 as protests of China’s betrayal by her so-called western allies at the post-World War 1 peace conference in Versailles, France. The Chinese had appealed to the western negotiators to restore German-occupied Shandong Peninsula back to China. When the imperialist allies gave the territory to imperialist Japan instead, it felt like the beginning of even deeper humiliation, and a longer delay to ending the twin oppressions of feudalism and imperialism. But the Chinese students were also inspired and fired up by news of the Russian Revolution, and the possibility that Marxism and communism could finally save China. The display makes clear that the students were fighting for science and reason and democracy against the oppressive forces that had overwhelmed China since its defeat in the Opium War of the mid-1800s. This set of progressive principles were the cornerstones of the nascent red movement that gave birth to the Communist Party of China two years later in 1921. It’s a reminder that for Chinese people, democracy and communism have always been essentially the same.

5. The “Mandate of Heaven”

Visiting Beijing inspires consideration of the ancient Chinese concept of “heavenly mandate” or “heavenly-invoked order,” which was recently explained by Tings Chak, editor of Dongsheng News, and author of Serve the People — The Eradication of Extreme Poverty in China. That study, released in 2021, documents China’s targeted program to eradicate extreme poverty among more than 800 million people, or more than half China’s entire population. Tings Chak explains that the so-called “heavenly mandate,” called “tianxia” in Chinese, is a way to describe the “shared aspirations of the people.” To claim political legitimacy, a ruler must have earned the support of “all under heaven.”

This quasi-mystical description is not exactly political science. It’s a philosophical expression of an effort by China’s Communist Party leadership to integrate Marxism with a millennial tradition of enlightened leadership. The CPC’s Institute of Party History and Literature is “drawing upon the Chinese concept of the people as the foundation of the state, the idea of universal participation in governance, the tradition of joint and consultative governance, and the political wisdom of being all-inclusive and seeking common ground while setting aside differences.”

In political practice these ideas form the basis of the people’s congresses at local, provincial and national levels, and the system of CPC-led multiparty cooperation and political consultation. Delegates to the local congresses are chosen through general elections. These delegates then vote for the provincial delegates, who in turn vote for national delegates. The National People’s Congress chooses the State Council, which has overall governing responsibility. CPC members and leaders play an active role at all these levels. The party itself has its own separate and parallel process, which can often be integrated with the non-party process. In practice, local party secretaries often serve as mayors or other local and regional government functionaries. There is also a system of regional ethnic autonomy, meant to assure self-determination for China’s fifty-five distinct ethnic groups.

“According to Confucius,” Tings Chak explains, the mandate system is voluntary and non-coercive. That’s important for social harmony both internally in China, and externally in its relationships with other countries. “States outside [the system] can participate if they deem it beneficial to them… Confucius suggested that the way to attract people outside [the system] is to satisfy the needs of the people already within it.” The approach is based on “seeking prosperity for all and harmony between all nations.” Recent developments, like the burgeoning Belt and Road Initiative and the BRICS trading network provide a sense of the core Chinese message: “common prosperity for a shared future.”

So what about police? Back in New York, one person cautioned me not to get arrested — be careful! I doubt he was basing his worries on experience in China, but rather on a widely held notion of a super-repressive police state where you risk getting arrested for jaywalking or denouncing injustice. In New York, of course, we jaywalk whenever and wherever we want, without fear of arrest, except for “walking while Black.” We barely saw police at all in Shanghai or Beijing, and very few more in Xinjiang, despite continued concerns of possible unrest there, as I explain in a separate report, “Eyewitness Xinjiang.” Our guide told us a large crowd of police showed up to monitor Halloween activities in Shanghai. But nothing happened.

So how does the party participate in society, and exercise leadership? Its roughly 95 million members range in social function from government officials at all levels, to researchers and teachers in universities, government agencies and think tanks, public school teachers and administrators, union leaders and ordinary workers. When we rode the bullet train from Shanghai to Beijing our guide pointed out train conductors wearing party tags. In addition to workforce participation, there are party members who manage state-owned enterprises (SOE’s), and others who sit on boards or management teams of private companies. (Private companies constitute a bit over half of the national economy.) Young people who do well in school are often recruited into the Young Communist League — the first rung for developing leaders. The same can happen in workplaces, where people with leadership skills can be “hand-picked” for party membership.

Most people are not party members. Their lives are “normal,” whether they’re students, workers or professionals. They’re the ones the party is pledged to serve. Polls and surveys have found that over 90 percent of the population trusts and approves of the government, according to a recent Harvard University study. But that does not mean everybody is happy. Our guide said there’s a vocal rightwing, especially among those that “got rich first” during Reform and Opening Up. Now they chafe at intensified government policies emphasizing common prosperity, and reining in the privileges and power that can come with being a billionaire, or even a well-off member of the professional or business classes. Others worry that cozy relationships they have nurtured with local government development planners will wither away. Being still determines consciousness, even in a “moderately prosperous socialist society.” And there are plenty of people in China that just worry about the danger of head-to-head conflict with Uncle Sam. Sanctions cut into some people’s business prospects, which can be more than a simple headache.

So the “heavenly mandate” isn’t always a bed of roses. But it’s the philosophic principle the national leadership is striving for.

6. Hunan

Most tourists go to Hunan to see its amazing natural beauty and taste its exotic, spicy cuisine. But for “red tourists” like us, the birthplace and childhood residence of Mao Zedong was the main attraction, along with a huge granite statue (105 feet high) of the 32-year-old Mao from when he was the leader of the infant Communist Party in Hunan. We were not alone. Even though it was a rainy weekday, crowds of local residents gathered to show respect to the founding leader of New China. Old folks like us lined up, many with teary eyes, others reverently chanting or even bowing in prayer-like obeisance. School children in blue and white uniforms marched in long lines toward the statue. Our guide told us the crowd was not remarkable or unusual — it’s a daily occurrence. On special days, like China’s October 1 national day, or Mao’s birthday, December 26, the crowds can swell to thousands.

We joined the line to walk through Mao’s childhood residence — a “rich man’s home”, since each child had a separate bedroom. Our guide told us young Mao Zedong was a rebellious teenager, often refusing to wash dishes or do other household chores because of his interest in studying. He got along well with his favorite teacher at the nearby school, and married the teacher’s daughter, with whom he fostered three children. One of them died in the Korean war, as related in the movie, The Battle of Lake Changjin.

Changsha, Hunan’s capital city, has a population of ten million, about the size of New York City. Its rows of apartment towers, 30 to 40 stories high, stretch for miles along the banks of the Xiangjiang River that passes through the city. Its “downtown” is a welter of mainly new skyscraper buildings that house a mix of foreign and domestic companies. Our guide proudly informed us that Changsha is an industrial powerhouse, with steel mills and auto factories. It is also home to the ancient art of textile embroidery. But it’s most famous as an intellectual center, with more than a hundred research institutions and engineering laboratories. A massive statue of Beethoven rises to the skyline above Orange Island, in the middle of the Xiangjiang River. (That’s right — Beethoven!) Hybrid rice breeding is one of the major achievements — important because it has increased China’s ability to produce enough rice to feed its people.

Our guide told us Hunan is a “source point” on China’s Belt and Road. Railroad links take steel rails from the factory in Changsha to points along the old Silk Road. But internet marketing makes it possible to send whole factories and even trains to other countries along the road, as well as engineers. She said some young people prefer to set up individual enterprises to sell products over the internet. They can sell anything from fine embroidery to cigarettes and even cars.

There’s a tradition in Hunan, going back centuries, of volunteering for national defense. That tradition may have been a factor in Mao’s decision to try and save his country. And it might explain the reverent respect the people of Hunan have for him.

We made friends with some people in Changsa who enjoyed talking with us about the world situation. They wanted to know if young people in the US think the same about China as the government. We explained there is lots of confusion among all people in our country, but that many young people are worried about the planet, and the future for themselves and their children. We agreed that the possibility of continued war — especially nuclear war — is an even greater danger. I made a promise to tell everyone I can reach in the US that the Chinese people do not want war.

Dee Knight is a member of the Bronx Antiwar Coalition, as well as the International Committee of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). He is the author of A Realistic Path to Peace, and a political memoir, My Whirlwind Lives.

Originally published at

https://deeknight.blog

on November 14, 2023.